Suzette

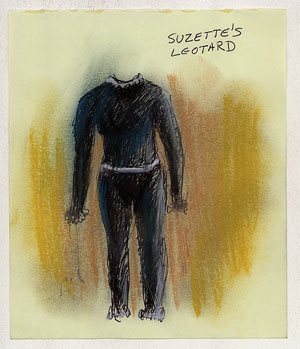

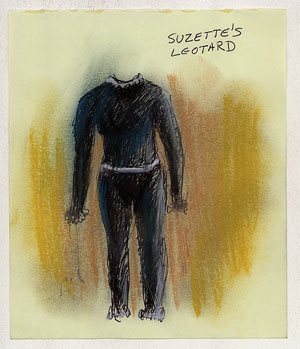

An apprentice in the Castle, serving under the tutelage of the wizard Toma, Suzette wears the standard apprentice’s outfit of black form-fitting leotards. Female apprentices are permitted a silver fringe of lace at their collar, their cuffs and their ankles, and may also wear a short skirt.

The status of the apprentice is indicated by the color of the belt worn at the waist. Apprentices with one to three years of service wear a brown belt. Those with four to six years of service wear a silver belt, and those with seven to nine years of service wear a gold belt.

Apprentices are not permitted to wear weapons of any sort while in service to the Castle. Thornwaldt’s insistence to Toma that he present his throwing knife to Suzette, while the adventurers are lost in the deep woods above Njording, takes on a significance, then, that has otherwise been lost in the several modern accounts of the story.

In pressing his weapon upon the young apprentice, the magician is committing a further act of `Defiance of the Emperor’, a crime punishable by public disembowelment. Even the enchantress, Grynwalt, responsive to the urgency of the moment, joins with Thornwaldt in insisting that Suzette be presented a weapon with which to defend herself, should the need arise.

The legal scholar Makademius argued that the magician had hardly put himself in greater jeopardy by this act, than he had in proposing the expedition in the first place, on the grounds that “a man cannot be disemboweled twice” (See: Makademius, “Questions Arising From the Multiple Acts of Treason Against the Emperor, Committed by the Defendant, called `The Instigator’; Fully Examined and Answered, and Entered into Evidence.”)

(But, see also the legal scholar Belemachis, in his reply, “Further Questions Regarding the Compounding of Sinfulness, for the Prosecution; A Brief Entered into as a Friend of the Court”, wherein he argues that, though a man may not be disemboweled more than once, he may have the limbs with which he committed the crime first removed from his body, and then, what is left may be subjected to disembowelment.)

(See also the moral philosopher Khalakhis who argues, in “A Considered Discussion of the Efficacy of Torture as Moral Agent, by which, Through the Mortification of the Body, the Soul is Spared Eternal Damnation and The Right Children of God are Spared Undue Suffering at the Hands of the Unrepentant” that “… it is not needed to seek the absolute mortification of the individual, i.e. the state we call `death’, nor even the cessation of vital functions of the organs – heart, lungs, liver, kidneys or spleen, and et cetera – nor does the inquisitor seek pleasure at the suffering of the unrepentant, but does all solely to preserve the immortal and sacred soul. Thus it is that the inquisitor seeks to inflict torture, only with the best of all possible intentions, and only to save the soul of the unrepentant… Thus, further, is it the case that the inquisitor seeks to avoid causing extreme mortification, (i.e., `death’, from above) but only to heighten the sensitivities of the unrepentant, that he (or she) may be more malleable and receptive to the state of grace which he, the inquisitor, seeks to impose… so amputation and disembowelment are to be considered techniques to be used in the most adamant and unrelenting of cases…

where mere mutilation will be sufficient to provoke the desired response… as most men are sensitive to their private parts, and as these private parts lead the unchaste to copious sinfulness, mutilation of said parts prior to execution is a profoundly salutary act – even one of kindness – in making the unrepentant properly humbled, thus preparing them for their entry into the eternal world, and wiping them clean of all sinfulness that may otherwise accrue to them…”)